We Shall Not Be Moved (2024)

74% User Rating

1h 37min

"An Absurd Plan of Revenge."

Socorro is a lawyer obsessed with finding the soldier who killed her brother during the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre. When she receives a crucial clue about the soldier’s whereabouts fifty years after her brother’s death, Socorro embarks on a reckless mission for revenge.

Pierre Saint Martin CastellanosDirector

Reviews (3)

All ReviewsB

Brent Marchant

Rating 80%

December 3, 2025

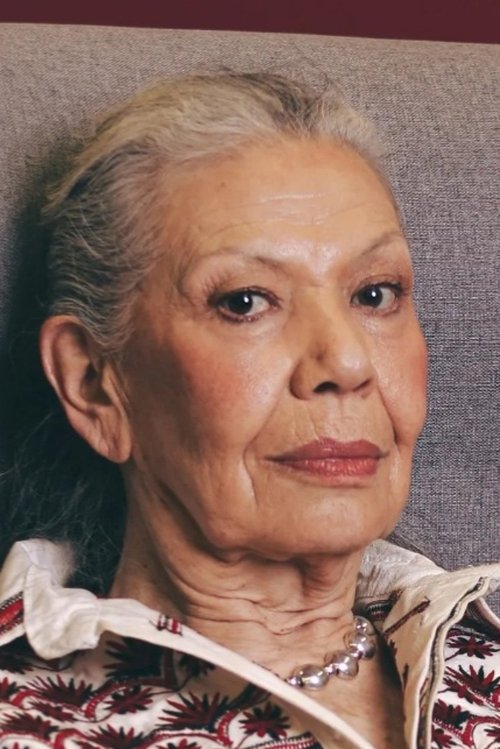

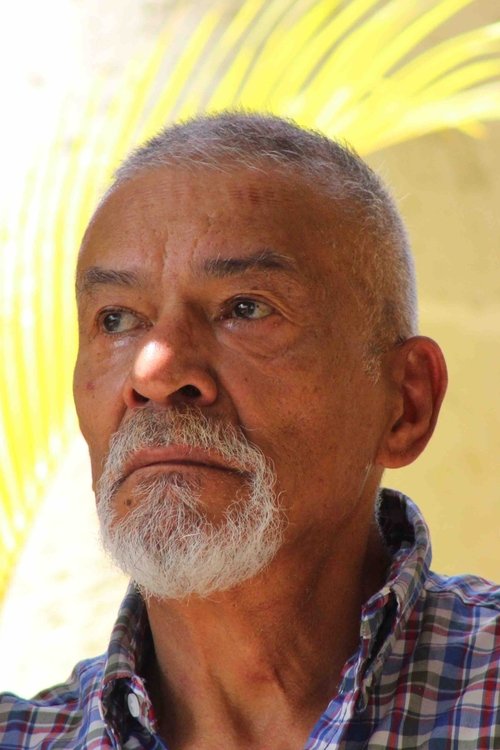

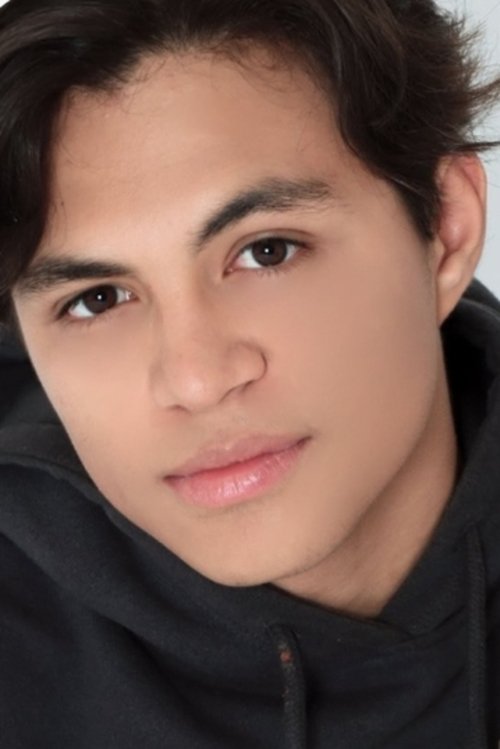

Whether or not we realize or acknowledge it, our memories can have considerable impact on us, perhaps even going so far as to define our character and drive our motivations, for better or worse. This is especially true when it comes to significantly powerful recollections, the kind that leave a profound, lasting impression on us and our psyche. But are these remembrances fixed and unalterable, essentially representing unshakable, infallible records of past experiences? Or can they shift over time, despite perpetual reinforcement that makes them seem like they’re fundamentally unchangeable? And how does that affect us in terms of our character, perspective and actions? Those are among the questions raised in this debut feature from writer-director Pierre Saint-Martin Castellanos, a fact-based memoir about his mother and a trauma she underwent in her youth. Retired Mexico City lawyer Socorro Castellanos (Luisa Huertas) leads a rather unfulfilling life in her cramped, rundown high-rise, sharing an apartment with a sister she despises (Rebeca Manríquez), her unemployed ne’er-do-well son (Pedro Hernández) and his industrious, inexplicably devoted wife (Agustina Quinci), a career woman who has become the couple’s principal breadwinner. Socorro had a long career skillfully maneuvering her way through Mexico’s corrupt political and legal system, but it’s worn down the gruff, surly, sometimes-ruthless counselor, contributing to the failing health and embittered outlook that have come to shape her everyday existence. But, more than that, she’s spent much of the past 50 years obsessing over the memory of her older brother’s killing at the hands of Mexican troops during the 1968 student protests at the Tlatelolco Massacre, one of the most violent event’s in the nation’s recent history. She has long sought her own brand of “justice” (i.e., vengeance) against the soldier responsible for his death, but all to no avail. However, when she comes upon a vital clue about her brother’s killer, she at last sees an opportunity to exact revenge. With the aid of the building’s jovial but untrustworthy janitor (José Alberto Patiño), a criminal whom she helped keep out of jail, Socorro hatches a plan to take down the alleged killer. But is this a wise idea? Is it a genuinely foolproof scheme? Is she sure of her facts? And has time hardened her memories to the point where she doesn’t question their accuracy? “We Shall Not Be Moved” provides an intriguing look at the question of how reliably we can trust our recollections, especially as we age and as infirmity, limitation and unyielding inflexibility begin to take their toll on our outlook and physical well-being. These themes are brought to bear through the film’s superb character development and stunning black-and-white cinematography, a fitting and gorgeous metaphor for the protagonist’s determined, unbending mindset. The picture’s devilish comic relief further enhances these attributes, providing the narrative with an edge that sharpens the story’s unapologetically bold sensibilities. It may take a little effort to find this independent gem, which has principally been playing at film festivals and in special screenings, but the filmmaker’s premiere effort is well worth it, a thoughtful production from a promising new talent.

Media